At first glance, the petal of a flower or the skin on the back of a human hand may seem smooth and seamless, as if they were composed of a single, indistinct substance. In reality, however, many tiny individual units called cells make up these objects and almost all other components of plants and animals. The average human body contains over 75 trillion cells, but many life forms exist as single cells that perform all the functions necessary for independent existence. Most cells are far too small to be seen with the naked eye and require the use of high-power optical and electron microscopes for careful examination.

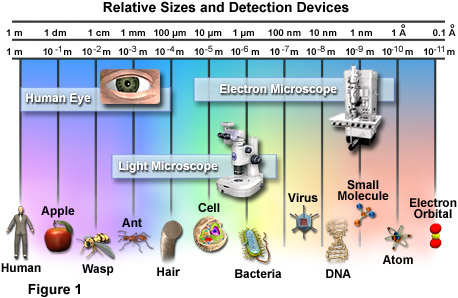

The relative scale of biological organisms as well as the useful range of several different detection devices is illustrated in Figure 1. The most basic image sensor, the eye, was the only means humans had of visually observing the world around them for thousands of years. Though excellent for viewing a wide variety of objects, the power of the eye has its limits, anything smaller than the width of a single human hair being able to pass unnoticed by the organ. Therefore, when light microscopes of sufficient magnifying capability were developed in the late 1600s, a whole new world of tiny wonders was discovered. Electron microscopes, invented in the mid-twentieth century, made it possible to detect even tinier objects than light microscopes, including smaller molecules, viruses, and DNA. The detection power of most electron microscopes used today, however, stops just short of being able to visualize such incredibly small structures as the electron orbital systems of individual atoms. Atoms are considered the smallest units of an element that have the characteristics of that element, but cells are the smallest structural units of an organism capable of functioning independently.

Yet, until the mid-seventeenth century, scientists were unaware that cells even existed. It wasn't until 1665 that biologist Robert Hooke observed through his microscope that plant tissues were divided into tiny compartments, which he termed "cellulae" or cells. It took another 175 years, however, before scientists began to understand the true importance of cells. In their studies of plant and animal cells during the early nineteenth century, German botanist Matthias Jakob Schleiden and German zoologist Theodor Schwann recognized the fundamental similarities between the two cell types. In 1839, they proposed that all living things are made up of cells, the theory that gave rise to modern biology.

Since that time, biologists have learned a great deal about the cell and its parts; what it is made of, how it functions, how it grows, and how it reproduces. The lingering question that is still being actively investigated is how cells evolved, i.e., how living cells originated from nonliving chemicals.

Numerous scientific disciplines—physics, geology, chemistry, and evolutionary biology—are being used to explore the question of cellular evolution. One theory speculates that substances vented into the air by volcanic eruptions were bombarded by lightning and ultraviolet radiation, producing larger, more stable molecules such as amino acids and nucleic acids. Rain carried these molecules to the Earth's surface where they formed a primordial soup of cellular building blocks.

A second theory proposes that cellular building blocks were formed in deep-water hydrothermal vents rather than in puddles or lakes on the Earth's surface. A third theory speculates that these key chemicals fell to earth on meteorites from outer space.

Given the basic building blocks and the right conditions, it would seem to be just a matter of time before cells begin to form. In the laboratory, lipid (fat) molecules have been observed joining together to produce spheres that are similar to a cell's plasma membrane. Over millions of years, perhaps it is inevitable that random collisions of lipid spheres with simple nucleic acids, such as RNA, would result in the first primitive cells capable of self-replication.

For all that has been learned about cells in over 300 years, hardly the least of which is the discovery of genetic inheritance and DNA, cell biology is still an exciting field of investigation. One recent addition is the study of how physical forces within the cell interact to form a stable biomechanical architecture. This is called "tensegrity" (a contraction of "tensional integrity"), a concept and word originally coined by Buckminster Fuller. The word refers to structures that are mechanically stable because stresses are distributed and balanced throughout the entire structure, not because the individual components have great strength.

In the realm of living cells, tensegrity is helping to explain how cells withstand physical stresses, how they are affected by the movements of organelles, and how a change in the cytoskeleton initiates biochemical reactions or even influences the action of genes. Some day, tensegrity may even explain the mechanical rules that caused molecules to assemble themselves into the first cells.

Animal Cells - Animal cells are typical of the eukaryotic cell type, enclosed by a plasma membrane and containing a membrane-bound nucleus and organelles.

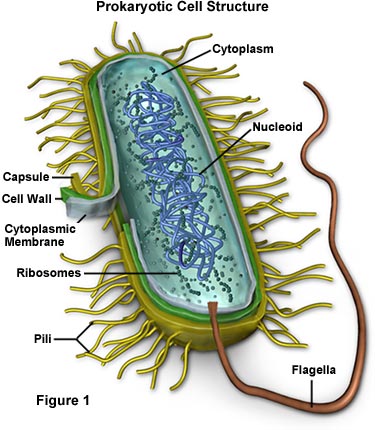

Bacteria - One of the earliest prokaryotic cells to have evolved, bacteria have been around for at least 3.5 billion years and live in almost every imaginable environment.

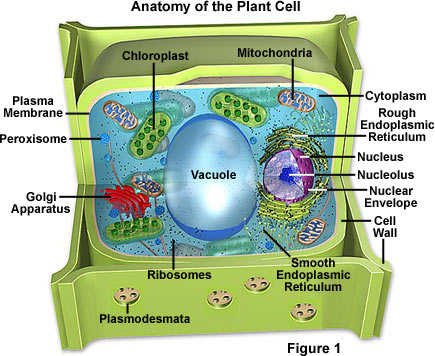

Plant Cells - The basic plant cell has a similar construction to the animal cell, but does not have centrioles, lysosomes, cilia, or flagella. It does have additional structures, including a rigid cell wall, central vacuole, plasmodesmata, and chloroplasts.

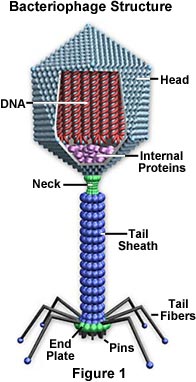

Virus Structure - Viruses are not alive in the strict sense of the word, but reproduce and have an intimate, if parasitic, relationship with all living organisms.

Cells in Motion - In multicellular tissues, such as those found in animals and humans, individual cells employ a variety of locomotion mechanisms to maneuver through spaces in the extracellular matrix and over the surfaces of other cells. Examples are the rapid movement of cells in developing embryos, organ-to-organ spreading of malignant cancer cells, and the migration of neural axons to synaptic targets. Unlike single-celled swimming organisms, crawling cells in culture do not possess cilia or flagella, but tend to move by coordinated projection of the cytoplasm in repeating cycles of extension and retraction that deform the entire cell. The digital videos presented in this gallery investigate animal cell motility patterns in a wide variety of morphologically different specimens.

Fluorescence Microscopy of Cells in Culture - Serious attempts at the culture of whole tissues and isolated cells were first undertaken in the early 1900s as a technique for investigating the behavior of animal cells in an isolated and highly controlled environment. The term tissue culture arose because most of the early cells were derived from primary tissue explants, a technique that dominated the field for over 50 years. As established cell lines emerged, the application of well-defined normal and transformed cells in biomedical investigations has become an important staple in the development of cellular and molecular biology. This fluorescence image gallery explores over 30 of the most common cell lines, labeled with a variety of fluorophores using both traditional staining methods as well as immunofluorescence techniques.

Observing Mitosis with Fluorescence Microscopy - Mitosis, a phenomenon observed in all higher eukaryotes, is the mechanism that allows the nuclei of cells to split and provide each daughter cell with a complete set of chromosomes during cellular division. This, coupled with cytokinesis (division of the cytoplasm), occurs in all multicellular plants and animals to permit growth of the organism. Digital imaging with fluorescence microscopy is becoming a powerful tool to assist scientists in understanding the complex process of mitosis on both a structural and functional level.

Cell Digestion and the Secretory Pathway - The primary sites of intracellular digestion are organelles known as the lysosomes, which are membrane-bounded compartments containing a variety of hydrolytic enzymes. Lysosomes maintain an internal acidic environment through the use of a hydrogen ion pump in the lysosomal membrane that drives ions from the cytoplasm into the lumenal space of the organelles. The high internal acidity is necessary for the enzymes contained in lysosomes to exhibit their optimum activity. Hence, if the integrity of a lysosomal membrane is compromised and the enzymatic contents are leaked into the cell, little damage is done due to the neutral pH of the cytoplasm. If numerous lysosomes rupture simultaneously, however, the cumulative action of their enzymes can result in autodigestion and the death of the cell.

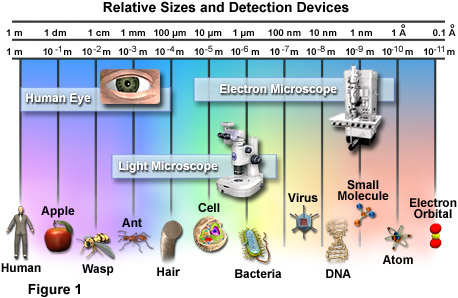

Animal Cell Structure

Animal cells are typical of the eukaryotic cell, enclosed by a plasma membrane and containing a membrane-bound nucleus and organelles. Unlike the eukaryotic cells of plants and fungi, animal cells do not have a cell wall. This feature was lost in the distant past by the single-celled organisms that gave rise to the kingdom Animalia. Most cells, both animal and plant, range in size between 1 and 100 micrometers and are thus visible only with the aid of a microscope.

The lack of a rigid cell wall allowed animals to develop a greater diversity of cell types, tissues, and organs. Specialized cells that formed nerves and muscles—tissues impossible for plants to evolve—gave these organisms mobility. The ability to move about by the use of specialized muscle tissues is a hallmark of the animal world, though a few animals, primarily sponges, do not possess differentiated tissues. Notably, protozoans locomote, but it is only via nonmuscular means, in effect, using cilia, flagella, and pseudopodia.

The animal kingdom is unique among eukaryotic organisms because most animal tissues are bound together in an extracellular matrix by a triple helix of protein known as collagen. Plant and fungal cells are bound together in tissues or aggregations by other molecules, such as pectin. The fact that no other organisms utilize collagen in this manner is one of the indications that all animals arose from a common unicellular ancestor. Bones, shells, spicules, and other hardened structures are formed when the collagen-containing extracellular matrix between animal cells becomes calcified.

Animals are a large and incredibly diverse group of organisms. Making up about three-quarters of the species on Earth, they run the gamut from corals and jellyfish to ants, whales, elephants, and, of course, humans. Being mobile has given animals, which are capable of sensing and responding to their environment, the flexibility to adopt many different modes of feeding, defense, and reproduction. Unlike plants, however, animals are unable to manufacture their own food, and therefore, are always directly or indirectly dependent on plant life.

Most animal cells are diploid, meaning that their chromosomes exist in homologous pairs. Different chromosomal ploidies are also, however, known to occasionally occur. The proliferation of animal cells occurs in a variety of ways. In instances of sexual reproduction, the cellular process of meiosis is first necessary so that haploid daughter cells, or gametes, can be produced. Two haploid cells then fuse to form a diploid zygote, which develops into a new organism as its cells divide and multiply.

The earliest fossil evidence of animals dates from the Vendian Period (650 to 544 million years ago), with coelenterate-type creatures that left traces of their soft bodies in shallow-water sediments. The first mass extinction ended that period, but during the Cambrian Period which followed, an explosion of new forms began the evolutionary radiation that produced most of the major groups, or phyla, known today. Vertebrates (animals with backbones) are not known to have occurred until the early Ordovician Period (505 to 438 million years ago).

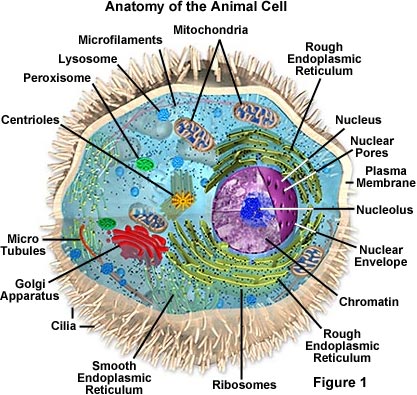

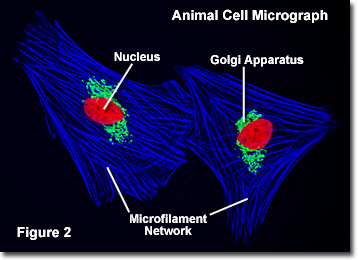

Cells were discovered in 1665 by British scientist Robert Hooke who first observed them in his crude (by today's standards) seventeenth century optical microscope. In fact, Hooke coined the term "cell", in a biological context, when he described the microscopic structure of cork like a tiny, bare room or monk's cell. Illustrated in Figure 2 are a pair of fibroblast deer skin cells that have been labeled with fluorescent probes and photographed in the microscope to reveal their internal structure. The nuclei are stained with a red probe, while the Golgi apparatus and microfilament actin network are stained green and blue, respectively. The microscope has been a fundamental tool in the field of cell biology and is often used to observe living cells in culture. Use the links below to obtain more detailed information about the various components that are found in animal cells.

· Centrioles - Centrioles are self-replicating organelles made up of nine bundles of microtubules and are found only in animal cells. They appear to help in organizing cell division, but aren't essential to the process.

· Cilia and Flagella - For single-celled eukaryotes, cilia and flagella are essential for the locomotion of individual organisms. In multicellular organisms, cilia function to move fluid or materials past an immobile cell as well as moving a cell or group of cells.

· Endoplasmic Reticulum - The endoplasmic reticulum is a network of sacs that manufactures, processes, and transports chemical compounds for use inside and outside of the cell. It is connected to the double-layered nuclear envelope, providing a pipeline between the nucleus and the cytoplasm.

· Endosomes and Endocytosis - Endosomes are membrane-bound vesicles, formed via a complex family of processes collectively known as endocytosis, and found in the cytoplasm of virtually every animal cell. The basic mechanism of endocytosis is the reverse of what occurs during exocytosis or cellular secretion. It involves the invagination (folding inward) of a cell's plasma membrane to surround macromolecules or other matter diffusing through the extracellular fluid.

· Golgi Apparatus - The Golgi apparatus is the distribution and shipping department for the cell's chemical products. It modifies proteins and fats built in the endoplasmic reticulum and prepares them for export to the outside of the cell.

· Intermediate Filaments - Intermediate filaments are a very broad class of fibrous proteins that play an important role as both structural and functional elements of the cytoskeleton. Ranging in size from 8 to 12 nanometers, intermediate filaments function as tension-bearing elements to help maintain cell shape and rigidity.

· Lysosomes - The main function of these microbodies is digestion. Lysosomes break down cellular waste products and debris from outside the cell into simple compounds, which are transferred to the cytoplasm as new cell-building materials.

· Microfilaments - Microfilaments are solid rods made of globular proteins called actin. These filaments are primarily structural in function and are an important component of the cytoskeleton.

· Microtubules - These straight, hollow cylinders are found throughout the cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells (prokaryotes don't have them) and carry out a variety of functions, ranging from transport to structural support.

· Mitochondria - Mitochondria are oblong shaped organelles that are found in the cytoplasm of every eukaryotic cell. In the animal cell, they are the main power generators, converting oxygen and nutrients into energy.

· Nucleus - The nucleus is a highly specialized organelle that serves as the information processing and administrative center of the cell. This organelle has two major functions: it stores the cell's hereditary material, or DNA, and it coordinates the cell's activities, which include growth, intermediary metabolism, protein synthesis, and reproduction (cell division).

· Peroxisomes - Microbodies are a diverse group of organelles that are found in the cytoplasm, roughly spherical and bound by a single membrane. There are several types of microbodies but peroxisomes are the most common.

· Plasma Membrane - All living cells have a plasma membrane that encloses their contents. In prokaryotes, the membrane is the inner layer of protection surrounded by a rigid cell wall. Eukaryotic animal cells have only the membrane to contain and protect their contents. These membranes also regulate the passage of molecules in and out of the cells.

· Ribosomes - All living cells contain ribosomes, tiny organelles composed of approximately 60 percent RNA and 40 percent protein. In eukaryotes, ribosomes are made of four strands of RNA. In prokaryotes, they consist of three strands of RNA.

In addition the optical and electron microscope, scientists are able to use a number of other techniques to probe the mysteries of the animal cell. Cells can be disassembled by chemical methods and their individual organelles and macromolecules isolated for study. The process of cell fractionation enables the scientist to prepare specific components, the mitochondria for example, in large quantities for investigations of their composition and functions. Using this approach, cell biologists have been able to assign various functions to specific locations within the cell. However, the era of fluorescent proteins has brought microscopy to the forefront of biology by enabling scientists to target living cells with highly localized probes for studies that don't interfere with the delicate balance of life processes.

They are as unrelated to human beings as living things can be, but bacteria are essential to human life and life on planet Earth. Although they are notorious for their role in causing human diseases, from tooth decay to the Black Plague, there are beneficial species that are essential to good health.

For example, one species that lives symbiotically in the large intestine manufactures vitamin K, an essential blood clotting factor. Other species are beneficial indirectly. Bacteria give yogurt its tangy flavor and sourdough bread its sour taste. They make it possible for ruminant animals (cows, sheep, goats) to digest plant cellulose and for some plants, (soybean, peas, alfalfa) to convert nitrogen to a more usable form.

Bacteria are prokaryotes, lacking well-defined nuclei and membrane-bound organelles, and with chromosomes composed of a single closed DNA circle. They come in many shapes and sizes, from minute spheres, cylinders and spiral threads, to flagellated rods, and filamentous chains. They are found practically everywhere on Earth and live in some of the most unusual and seemingly inhospitable places.

Evidence shows that bacteria were in existence as long as 3.5 billion years ago, making them one of the oldest living organisms on the Earth. Even older than the bacteria are the archeans (also called archaebacteria) tiny prokaryotic organisms that live only in extreme environments: boiling water, super-salty pools, sulfur-spewing volcanic vents, acidic water, and deep in the Antarctic ice. Many scientists now believe that the archaea and bacteria developed separately from a common ancestor nearly four billion years ago. Millions of years later, the ancestors of today's eukaryotes split off from the archaea. Despite the superficial resemblance to bacteria, biochemically and genetically, the archea are as different from bacteria as bacteria are from humans.

In the late 1600s, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek became the first to study bacteria under the microscope. During the nineteenth century, the French scientist Louis Pasteur and the German physician Robert Koch demonstrated the role of bacteria as pathogens (causing disease). The twentieth century saw numerous advances in bacteriology, indicating their diversity, ancient lineage, and general importance. Most notably, a number of scientists around the world made contributions to the field of microbial ecology, showing that bacteria were essential to food webs and for the overall health of the Earth's ecosystems. The discovery that some bacteria produced compounds lethal to other bacteria led to the development of antibiotics, which revolutionized the field of medicine.

There are two different ways of grouping bacteria. They can be divided into three types based on their response to gaseous oxygen. Aerobic bacteria require oxygen for their health and existence and will die without it. Anerobic bacteria can't tolerate gaseous oxygen at all and die when exposed to it. Facultative aneraobes prefer oxygen, but can live without it.

The second way of grouping them is by how they obtain their energy. Bacteria that have to consume and break down complex organic compounds are heterotrophs. This includes species that are found in decaying material as well as those that utilize fermentation or respiration. Bacteria that create their own energy, fueled by light or through chemical reactions, are autotrophs.

· Capsule - Some species of bacteria have a third protective covering, a capsule made up of polysaccharides (complex carbohydrates). Capsules play a number of roles, but the most important are to keep the bacterium from drying out and to protect it from phagocytosis (engulfing) by larger microorganisms. The capsule is a major virulence factor in the major disease-causing bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Nonencapsulated mutants of these organisms are avirulent, i.e. they don't cause disease.

· Cell Envelope - The cell envelope is made up of two to three layers: the interior cytoplasmic membrane, the cell wall, and -- in some species of bacteria -- an outer capsule.

· Cell Wall - Each bacterium is enclosed by a rigid cell wall composed of peptidoglycan, a protein-sugar (polysaccharide) molecule. The wall gives the cell its shape and surrounds the cytoplasmic membrane, protecting it from the environment. It also helps to anchor appendages like the pili and flagella, which originate in the cytoplasm membrane and protrude through the wall to the outside. The strength of the wall is responsible for keeping the cell from bursting when there are large differences in osmotic pressure between the cytoplasm and the environment.

Cell wall composition varies widely amongst bacteria and is one of the most important factors in bacterial species analysis and differentiation. For example, a relatively thick, meshlike structure that makes it possible to distinguish two basic types of bacteria. A technique devised by Danish physician Hans Christian Gram in 1884, uses a staining and washing technique to differentiate between the two forms. When exposed to a gram stain, gram-positive bacteria retain the purple color of the stain because the structure of their cell walls traps the dye. In gram-negative bacteria, the cell wall is thin and releases the dye readily when washed with an alcohol or acetone solution.

· Cytoplasm - The cytoplasm, or protoplasm, of bacterial cells is where the functions for cell growth, metabolism, and replication are carried out. It is a gel-like matrix composed of water, enzymes, nutrients, wastes, and gases and contains cell structures such as ribosomes, a chromosome, and plasmids. The cell envelope encases the cytoplasm and all its components. Unlike the eukaryotic (true) cells, bacteria do not have a membrane enclosed nucleus. The chromosome, a single, continuous strand of DNA, is localized, but not contained, in a region of the cell called the nucleoid. All the other cellular components are scattered throughout the cytoplasm.

· Cytoplasmic Membrane - A layer of phospholipids and proteins, called the cytoplasmic membrane, encloses the interior of the bacterium, regulating the flow of materials in and out of the cell. This is a structural trait bacteria share with all other living cells; a barrier that allows them to selectively interact with their environment. Membranes are highly organized and asymmetric having two sides, each side with a different surface and different functions. Membranes are also dynamic, constantly adapting to different conditions.

One of those components, plasmids, are small, extrachromosomal genetic structures carried by many strains of bacteria. Like the chromosome, plasmids are made of a circular piece of DNA. Unlike the chromosome, they are not involved in reproduction. Only the chromosome has the genetic instructions for initiating and carrying out cell division, or binary fission, the primary means of reproduction in bacteria. Plasmids replicate independently of the chromosome and, while not essential for survival, appear to give bacteria a selective advantage.

Plasmids are passed on to other bacteria through two means. For most plasmid types, copies in the cytoplasm are passed on to daughter cells during binary fission. Other types of plasmids, however, form a tubelike structure at the surface called a pilus that passes copies of the plasmid to other bacteria during conjugation, a process by which bacteria exchange genetic information. Plasmids have been shown to be instrumental in the transmission of special properties, such as antibiotic drug resistance, resistance to heavy metals, and virulence factors necessary for infection of animal or plant hosts. The ability to insert specific genes into plasmids have made them extremely useful tools in the fields of molecular biology and genetics, specifically in the area of genetic engineering.

· Flagella - Flagella (singular, flagellum) are hairlike structures that provide a means of locomotion for those bacteria that have them. They can be found at either or both ends of a bacterium or all over its surface. The flagella beat in a propeller-like motion to help the bacterium move toward nutrients; away from toxic chemicals; or, in the case of the photosynthetic cyanobacteria; toward the light.

· Nucleoid - The nucleoid is a region of cytoplasm where the chromosomal DNA is located. It is not a membrane bound nucleus, but simply an area of the cytoplasm where the strands of DNA are found. Most bacteria have a single, circular chromosome that is responsible for replication, although a few species do have two or more. Smaller circular auxiliary DNA strands, called plasmids, are also found in the cytoplasm.

· Pili - Many species of bacteria have pili (singular, pilus), small hairlike projections emerging from the outside cell surface. These outgrowths assist the bacteria in attaching to other cells and surfaces, such as teeth, intestines, and rocks. Without pili, many disease-causing bacteria lose their ability to infect because they're unable to attach to host tissue. Specialized pili are used for conjugation, during which two bacteria exchange fragments of plasmid DNA.

· Ribosomes - Ribosomes are microscopic "factories" found in all cells, including bacteria. They translate the genetic code from the molecular language of nucleic acid to that of amino acids—the building blocks of proteins. Proteins are the molecules that perform all the functions of cells and living organisms. Bacterial ribosomes are similar to those of eukaryotes, but are smaller and have a slightly different composition and molecular structure. Bacterial ribosomes are never bound to other organelles as they sometimes are (bound to the endoplasmic reticulum) in eukaryotes, but are free-standing structures distributed throughout the cytoplasm. There are sufficient differences between bacterial ribosomes and eukaryotic ribosomes that some antibiotics will inhibit the functioning of bacterial ribosomes, but not a eukaryote's, thus killing bacteria but not the eukaryotic organisms they are infecting.

Plants are unique among the eukaryotes, organisms whose cells have membrane-enclosed nuclei and organelles, because they can manufacture their own food. Chlorophyll, which gives plants their green color, enables them to use sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugars and carbohydrates, chemicals the cell uses for fuel.

Like the fungi, another kingdom of eukaryotes, plant cells have retained the protective cell wall structure of their prokaryotic ancestors. The basic plant cell shares a similar construction motif with the typical eukaryote cell, but does not have centrioles, lysosomes, intermediate filaments, cilia, or flagella, as does the animal cell. Plant cells do, however, have a number of other specialized structures, including a rigid cell wall, central vacuole, plasmodesmata, and chloroplasts. Although plants (and their typical cells) are non-motile, some species produce gametes that do exhibit flagella and are, therefore, able to move about.

Plants can be broadly categorized into two basic types: vascular and nonvascular. Vascular plants are considered to be more advanced than nonvascular plants because they have evolved specialized tissues, namely xylem, which is involved in structural support and water conduction, and phloem, which functions in food conduction. Consequently, they also possess roots, stems, and leaves, representing a higher form of organization that is characteristically absent in plants lacking vascular tissues. The nonvascular plants, members of the division Bryophyta, are usually no more than an inch or two in height because they do not have adequate support, which is provided by vascular tissues to other plants, to grow bigger. They also are more dependent on the environment that surrounds them to maintain appropriate amounts of moisture and, therefore, tend to inhabit damp, shady areas.

It is estimated that there are at least 260,000 species of plants in the world today. They range in size and complexity from small, nonvascular mosses to giant sequoia trees, the largest living organisms, growing as tall as 330 feet (100 meters). Only a tiny percentage of those species are directly used by people for food, shelter, fiber, and medicine. Nonetheless, plants are the basis for the Earth's ecosystem and food web, and without them complex animal life forms (such as humans) could never have evolved. Indeed, all living organisms are dependent either directly or indirectly on the energy produced by photosynthesis, and the byproduct of this process, oxygen, is essential to animals. Plants also reduce the amount of carbon dioxide present in the atmosphere, hinder soil erosion, and influence water levels and quality.

Plants exhibit life cycles that involve alternating generations of diploid forms, which contain paired chromosome sets in their cell nuclei, and haploid forms, which only possess a single set. Generally these two forms of a plant are very dissimilar in appearance. In higher plants, the diploid generation, the members of which are known as sporophytes due to their ability to produce spores, is usually dominant and more recognizable than the haploid gametophyte generation. In Bryophytes, however, the gametophyte form is dominant and physiologically necessary to the sporophyte form.

Animals are required to consume protein in order to obtain nitrogen, but plants are able to utilize inorganic forms of the element and, therefore, do not need an outside source of protein. Plants do, however, usually require significant amounts of water, which is needed for the photosynthetic process, to maintain cell structure and facilitate growth, and as a means of bringing nutrients to plant cells. The amount of nutrients needed by plant species varies significantly, but nine elements are generally considered to be necessary in relatively large amounts. Termed macroelements, these nutrients include calcium, carbon, hydrogen, magnesium, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, potassium, and sulfur. Seven microelements, which are required by plants in smaller quantities, have also been identified: boron, chlorine, copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, and zinc.

Thought to have evolved from the green algae, plants have been around since the early Paleozoic era, more than 500 million years ago. The earliest fossil evidence of land plants dates to the Ordovician Period (505 to 438 million years ago). By the Carboniferous Period, about 355 million years ago, most of the Earth was covered by forests of primitive vascular plants, such as lycopods (scale trees) and gymnosperms (pine trees, ginkgos). Angiosperms, the flowering plants, didn't develop until the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 65 million years ago—just as the dinosaurs became extinct.

· Cell Wall - Like their prokaryotic ancestors, plant cells have a rigid wall surrounding the plasma membrane. It is a far more complex structure, however, and serves a variety of functions, from protecting the cell to regulating the life cycle of the plant organism.

· Chloroplasts - The most important characteristic of plants is their ability to photosynthesize, in effect, to make their own food by converting light energy into chemical energy. This process is carried out in specialized organelles called chloroplasts.

· Endoplasmic Reticulum - The endoplasmic reticulum is a network of sacs that manufactures, processes, and transports chemical compounds for use inside and outside of the cell. It is connected to the double-layered nuclear envelope, providing a pipeline between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. In plants, the endoplasmic reticulum also connects between cells via the plasmodesmata.

· Golgi Apparatus - The Golgi apparatus is the distribution and shipping department for the cell's chemical products. It modifies proteins and fats built in the endoplasmic reticulum and prepares them for export as outside of the cell.

· Microfilaments - Microfilaments are solid rods made of globular proteins called actin. These filaments are primarily structural in function and are an important component of the cytoskeleton.

· Microtubules - These straight, hollow cylinders are found throughout the cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells (prokaryotes don't have them) and carry out a variety of functions, ranging from transport to structural support.

· Mitochondria - Mitochondria are oblong shaped organelles found in the cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells. In plant cells, they break down carbohydrate and sugar molecules to provide energy, particularly when light isn't available for the chloroplasts to produce energy.

· Nucleus - The nucleus is a highly specialized organelle that serves as the information processing and administrative center of the cell. This organelle has two major functions: it stores the cell's hereditary material, or DNA, and it coordinates the cell's activities, which include growth, intermediary metabolism, protein synthesis, and reproduction (cell division).

· Peroxisomes - Microbodies are a diverse group of organelles that are found in the cytoplasm, roughly spherical and bound by a single membrane. There are several types of microbodies but peroxisomes are the most common.

· Plasmodesmata - Plasmodesmata are small tubes that connect plant cells to each other, providing living bridges between cells.

· Plasma Membrane - All living cells have a plasma membrane that encloses their contents. In prokaryotes and plants, the membrane is the inner layer of protection surrounded by a rigid cell wall. These membranes also regulate the passage of molecules in and out of the cells.

· Ribosomes - All living cells contain ribosomes, tiny organelles composed of approximately 60 percent RNA and 40 percent protein. In eukaryotes, ribosomes are made of four strands of RNA. In prokaryotes, they consist of three strands of RNA.

· Vacuole - Each plant cell has a large, single vacuole that stores compounds, helps in plant growth, and plays an important structural role for the plant.

Leaf Tissue Organization - The plant body is divided into several organs: roots, stems, and leaves. The leaves are the primary photosynthetic organs of plants, serving as key sites where energy from light is converted into chemical energy. Similar to the other organs of a plant, a leaf is comprised of three basic tissue systems, including the dermal, vascular, and ground tissue systems. These three motifs are continuous throughout an entire plant, but their properties vary significantly based upon the organ type in which they are located. All three tissue systems are discussed in this section.

Viruses are not plants, animals, or bacteria, but they are the quintessential parasites of the living kingdoms. Although they may seem like living organisms because of their prodigious reproductive abilities, viruses are not living organisms in the strict sense of the word.

Without a host cell, viruses cannot carry out their life-sustaining functions or reproduce. They cannot synthesize proteins, because they lack ribosomes and must use the ribosomes of their host cells to translate viral messenger RNA into viral proteins. Viruses cannot generate or store energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), but have to derive their energy, and all other metabolic functions, from the host cell. They also parasitize the cell for basic building materials, such as amino acids, nucleotides, and lipids (fats). Although viruses have been speculated as being a form of protolife, their inability to survive without living organisms makes it highly unlikely that they preceded cellular life during the Earth's early evolution. Some scientists speculate that viruses started as rogue segments of genetic code that adapted to a parasitic existence.

All viruses contain nucleic acid, either DNA or RNA (but not both), and a protein coat, which encases the nucleic acid. Some viruses are also enclosed by an envelope of fat and protein molecules. In its infective form, outside the cell, a virus particle is called a virion. Each virion contains at least one unique protein synthesized by specific genes in its nucleic acid. Viroids (meaning "viruslike") are disease-causing organisms that contain only nucleic acid and have no structural proteins. Other viruslike particles called prions are composed primarily of a protein tightly integrated with a small nucleic acid molecule.

Viruses are generally classified by the organisms they infect, animals, plants, or bacteria. Since viruses cannot penetrate plant cell walls, virtually all plant viruses are transmitted by insects or other organisms that feed on plants. Certain bacterial viruses, such as the T4 bacteriophage, have evolved an elaborate process of infection. The virus has a "tail" which it attaches to the bacterium surface by means of proteinaceous "pins." The tail contracts and the tail plug penetrates the cell wall and underlying membrane, injecting the viral nucleic acids into the cell. Viruses are further classified into families and genera based on three structural considerations: 1) the type and size of their nucleic acid, 2) the size and shape of the capsid, and 3) whether they have a lipid envelope surrounding the nucleocapsid (the capsid enclosed nucleic acid).

There are predominantly two kinds of shapes found amongst viruses: rods, or filaments, and spheres. The rod shape is due to the linear array of the nucleic acid and the protein subunits making up the capsid. The sphere shape is actually a 20-sided polygon (icosahedron).

The nature of viruses wasn't understood until the twentieth century, but their effects had been observed for centuries. British physician Edward Jenner even discovered the principle of inoculation in the late eighteenth century, after he observed that people who contracted the mild cowpox disease were generally immune to the deadlier smallpox disease. By the late nineteenth century, scientists knew that some agent was causing a disease of tobacco plants, but would not grow on an artificial medium (like bacteria) and was too small to be seen through a light microscope. Advances in live cell culture and microscopy in the twentieth century eventually allowed scientists to identify viruses. Advances in genetics dramatically improved the identification process.

· Capsid - The capsid is the protein shell that encloses the nucleic acid; with its enclosed nucleic acid, it is called the nucleocapsid. This shell is composed of protein organized in subunits known as capsomers. They are closely associated with the nucleic acid and reflect its configuration, either a rod-shaped helix or a polygon-shaped sphere. The capsid has three functions: 1) it protects the nucleic acid from digestion by enzymes, 2) contains special sites on its surface that allow the virion to attach to a host cell, and 3) provides proteins that enable the virion to penetrate the host cell membrane and, in some cases, to inject the infectious nucleic acid into the cell's cytoplasm. Under the right conditions, viral RNA in a liquid suspension of protein molecules will self-assemble a capsid to become a functional and infectious virus.

· Envelope - Many types of virus have a glycoprotein envelope surrounding the nucleocapsid. The envelope is composed of two lipid layers interspersed with protein molecules (lipoprotein bilayer) and may contain material from the membrane of a host cell as well as that of viral origin. The virus obtains the lipid molecules from the cell membrane during the viral budding process. However, the virus replaces the proteins in the cell membrane with its own proteins, creating a hybrid structure of cell-derived lipids and virus-derived proteins. Many viruses also develop spikes made of glycoprotein on their envelopes that help them to attach to specific cell surfaces.

· Nucleic Acid - Just as in cells, the nucleic acid of each virus encodes the genetic information for the synthesis of all proteins. While the double-stranded DNA is responsible for this in prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, only a few groups of viruses use DNA. Most viruses maintain all their genetic information with the single-stranded RNA. There are two types of RNA-based viruses. In most, the genomic RNA is termed a plus strand because it acts as messenger RNA for direct synthesis (translation) of viral protein. A few, however, have negative strands of RNA. In these cases, the virion has an enzyme, called RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (transcriptase), which must first catalyze the production of complementary messenger RNA from the virion genomic RNA before viral protein synthesis can occur.

The Influenza (Flu) Virus - Next to the common cold, influenza or "the flu" is perhaps the most familiar respiratory infection in the world. In the United States alone, approximately 25 to 50 million people contract influenza each year. The symptoms of the flu are similar to those of the common cold, but tend to be more severe. Fever, headache, fatigue, muscle weakness and pain, sore throat, dry cough, and a runny or stuffy nose are common and may develop rapidly. Gastrointestinal symptoms associated with influenza are sometimes experienced by children, but for most adults, illnesses that manifest in diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting are not caused by the influenza virus though they are often inaccurately referred to as the "stomach flu." A number of complications, such as the onset of bronchitis and pneumonia, can also occur in association with influenza and are especially common among the elderly, young children, and anyone with a suppressed immune system.

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) - The virus responsible for HIV was first isolated in 1983 by Robert Gallo of the United States and French scientist Luc Montagnier. Since that time, a tremendous amount of research focusing upon the causative agent of AIDS has been carried out and much has been learned about the structure of the virus and its typical course of action. HIV is one of a group of atypical viruses called retroviruses that maintain their genetic information in the form of ribonucleic acid (RNA). Through the use of an enzyme known as reverse transcriptase, HIV and other retroviruses are capable of producing deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from RNA, whereas most cells carry out the opposite process, transcribing the genetic material of DNA into RNA. The activity of the enzyme enables the genetic information of HIV to become integrated permanently into the genome (chromosomes) of a host cell.